White Gold is a work that attempts to look beyond its own personal sphere. In a time of general crisis, the sphere of the self and personal search are set aside, overshadowed by issues whose consequences immediately reveal their profound impact on the environment, climate, labor, healthcare, and society. The term 'extractivism' does not refer only to the extraction of natural resources but to a specific mode of capitalist operation, based on ‘the systematic removal of wealth from territories, combined with the transfer of sovereignty over them, from those who inhabit them to those who plunder them. Conflict, violence, military control of the territory, political-corporate collusion in which the state and the market are indistinguishable, extreme poverty and labor coercion, criminalization of dissent, systemic corruption. All these are not collateral damages [...] but the very conditions without which extractivism itself would not proliferate.

Like other places in the world, the province of Massa-Carrara is a disturbing emblem of this reductionism and a particularly clear example of how capitalism functions in its extractivist form. The images speak for themselves. Whether you arrive in the province from the north or south, from the sea or from the inland, the gaze cannot avoid the Apuan Alps, jagged mountains just a few kilometers from the sea, mostly unknown despite a unique ecosystem with UNESCO recognition.

Wonderful and fragile mountains because they are karstic: devastated, eaten, full of holes and wounds, sometimes truncated, devoured from within like by a monster to extract marble and reduce them to dust. Do we not then have, in capitalist society, a complete and highly contagious case of possession? Collective possession? A gigantic operation, not secret but in plain sight, of mental manipulation, behavioral influence through media, advertising, and architecture? Is it not through the spirit that we are primarily chained?

The things we prevent ourselves from doing or thinking, are they not perhaps torn from the root by a permanent and devastating conditioning of our thought? A militant recently said that the current climate and ecological crisis is, above all, a psychological problem. The discrepancy between our discourse, our values, and our actions is so great that it rightfully falls into the realm of mental pathology. What force can lead us to such denial and condemn us to such impotence, if not some sort of enchantment?

Capitalism is not just a way of organizing labor and production. It is a way of seeing the world, of conceiving ourselves and the reality we live in, of experiencing relationships: it is a complete cosmos. Domination and control, rather than reciprocity; the individual as closed and independent, rather than constituted by the relationship with everything around them; nature as an object, rather than part of ourselves; violent partition – these are its specific premises. To relegate such issues to the theoretical realm is part of the trick that prevents us from rethinking the entire system and conceiving others, new and different. Radical ecology today may have the strength to do what other paradigms failed to do in the past: to include the deeper dimensions of being in the political struggle for the claim and construction of better worlds. Through its lenses, the economic and political problem becomes ontological and epistemological. In the face of ecology, capitalist witchcraft begins to lose its power, to be less 'natural,' and the paper sky tears apart: it is evident even to us today, to us privileged ones, that this is not the best of all possible worlds and that reality, and above all life, respond to other logics and require other practices.

Carlo Perazzo, anthropologist, writer, activist, and Carrarino resident, in an article for the magazine ALTRAPAROLA, 'From Marble to Mountain: Capitalist Witchcraft, Extractivism, and Ecology in the Apuan Alps,' helps me understand how a problem of such vast scale can impact the everyday life of the population, even though it is concealed by false narratives. I realize how a local situation can mirror a complex and broader global mechanism, probably more deeply rooted in the

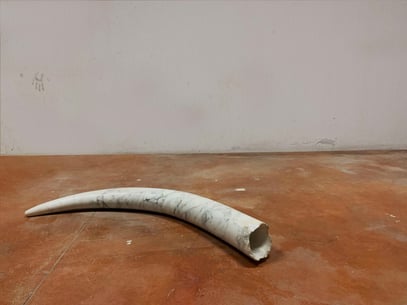

West, with the rest of the world, especially the Global South, hanging like puppets. The tusk becomes a synecdoche, a relic, a symbol of a beauty within which the darkest human parts are hidden.

Materials: Marble / Wax-Patinated Plaster

Single Dimensions: 120 x 50 x 15 cm

Location: Carrara, 2022

ORO BIANCO