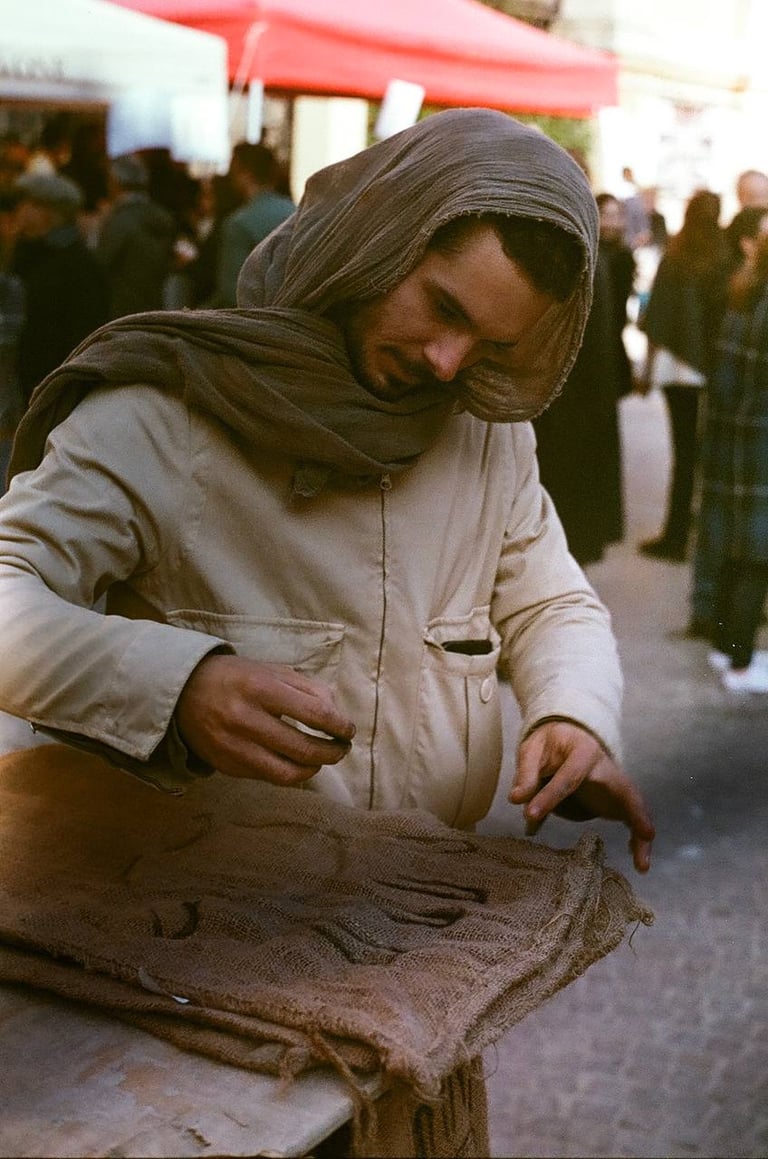

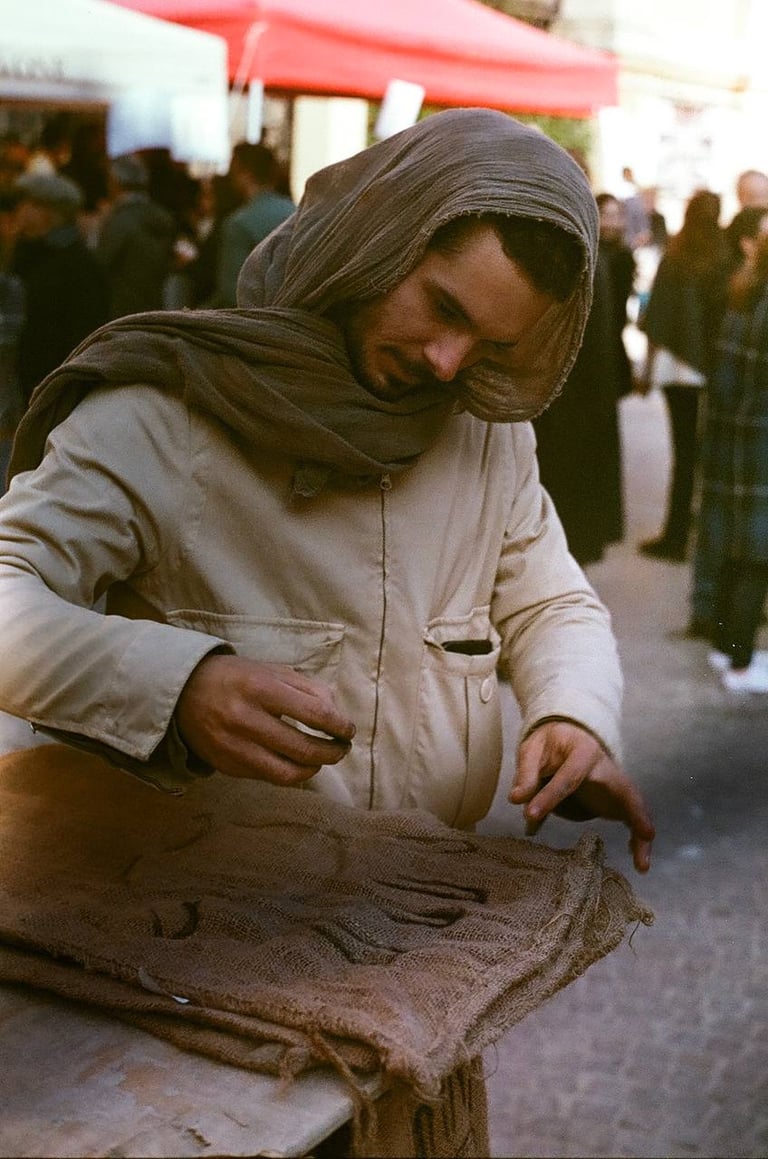

Giulia e Gianni all'interno del laboratorio della bottega

© photos: Greta Vanzi

Laboratorio: "pace al fango"

Festa della Solidarietà , laboratori ed installazione di "Sostegno"

English below

SOSTEGNO

Il racconto:

Giornata di Solidarietà a Bologna: La Risposta del quartiere all'Alluvione del 19-20 Ottobre 2024

L’alluvione che ha colpito l’Emilia-Romagna tra il 19 e il 20 ottobre 2024 ha devastato numerosi comuni, tra cui Bologna e la sua area metropolitana, causando danni ingenti a causa delle esondazioni di fiumi e torrenti e della pressione accumulata nei canali sotterranei. Una giovane vita è stata persa, mentre migliaia di persone sono state costrette ad abbandonare le proprie case.

Le intense piogge, che hanno scaricato in poche ore l’equivalente di due mesi di precipitazioni, hanno evidenziato la crescente vulnerabilità del territorio, aggravata dalla continua urbanizzazione e dal consumo di suolo. Questo fenomeno, acuito dai cambiamenti climatici, è diventato una tragica realtà ricorrente, come dimostrato dalla serie di alluvioni che hanno colpito la regione negli anni precedenti.

In risposta alla tragedia, le volontarie di Bologna sono stati chiamati a unirsi in un grande gesto di solidarietà. Il 10 novembre 2024, via Andrea Costa è stata trasformata in uno spazio di raccolta fondi, grazie alla festa di strada organizzata per sostenere le famiglie colpite dall’alluvione e offrire un segno tangibile di vicinanza. L’evento ha rappresentato la continuazione di un impegno cittadino che ha visto migliaia di persone coinvolte attivamente nelle giornate successive alla calamità, unendo le forze per ricostruire la città e aiutare le persone a riprendersi dalle devastazioni.

Sostegno è stato realizzato in via Andrea Costa, proprio in uno dei punti più colpiti dall’alluvione, tra due tratti in cui il fiume è esondato, facendo scoppiare la tombatura in cemento. Lì, tra le persone che aspettavano risposte dalle assicurazioni per capire se il danno potesse essere almeno in parte rimborsato, e il rusco che straripava dai marciapiedi, ancora gocciolante di fango.

Scendemmo nelle cantine, e c’era un segno dipinto sul muro, una linea che marcava il livello dell’acqua: arrivava fino al collo. Giorgio, un abitante di via del Q, dal quale fummo mandati per uno sgombero di cantine, ci raccontò che erano stati fortunati nel loro palazzo. L’acqua, senza che si capisse come, aveva trovato una via d’uscita, e nel giro di qualche ora dall’alluvione era defluita, lasciando solo spanne di fanghiglia. Arrivammo in molti. In quei giorni, la solidarietà fece miracoli. La parrocchia divenne il campo base, con punti di ristoro, banconi con stivali, copri-scarpe, guanti, zone per sciacquare via il fango, e spazi dove i volontari si radunavano per essere inviati dove c’era più bisogno. Tra i miracoli di quelle giornate ci fu l'abbattimento dei muri ideologici: vedere i gruppi di PLAT (Piattaforma di Intervento Sociale), che erano presi dall'occupazione di via dei Carracci Casa Comune — dove avevano dato casa a decine e decine di famiglie senza tetto e senza possibilità di averlo — e gli scout della parrocchia, con tanto di parroco in prima linea, fu un vedere da non credere.

Anche in via del Q, la situazione era difficile, ma la squadra con cui ero aveva un numero impressionante di persone. Si facevano le catene, e poche persone restavano nelle cantine, mentre le altre si passavano gli oggetti da buttare, accatastandoli lungo la strada. Arrivammo da Giorgio e i volontari dovevano ancora arrivare. Lungo la strada, una cantina che non aveva ricevuto danni ci offrì del vino, vedendoci tutti ricoperti di fango, identificandoci come volontari. Prima di iniziare a svuotare, ci fermammo a fare due chiacchiere con Giorgio, che ci mostrò le sue cantine: una piena di oggetti più recenti e l’altra con le botti, le bottiglie e tutta la strumentazione per fare il vino, che conservava per ricordo.

Il tono con cui ce lo raccontava creava una malinconia che riscaldava il cuore, quasi scottava. Tutto era da buttare. Iniziammo la catena, mentre altri volontari si aggregavano. Giorgio ci stava vicino, attento a quello che toccavamo e a cosa buttavamo, perché ogni oggetto per lui era un pezzo di vita, uno di quei ricordi custoditi con cura, ora sommersi dall’acqua e dal fango, portato via da giovani e ragazze. Si rassegnò al fatto che la maggior parte degli oggetti doveva essere gettata, ma ci disse con un sorriso che voleva fare pulizia da tempo e che forse questa era l’occasione giusta. Lo disse con un sorriso, contento di poter condividere quell’occasione con noi. Si rese conto che non era solo a dover svuotare la cantina, ma che decine di giovani erano lì, accanto a lui. Quella realizzazione si rifletteva nel suo volto in un preciso momento, e da lì i suoi occhi iniziarono a brillare.

Dopo qualche settimana tornai per far parte della giornata di solidarietà di raccolta fondi per Andrea Costa e i suoi abitanti. Passai una settimana a passeggiare per quelle vie, parlare con i commercianti, abitanti e passanti. Decisi di realizzare il lavoro lì, anche se mi avevano chiesto di realizzare un lavoro visibile in strada, che potesse comunicare con le persone e, quindi, che avesse anche una certa dimensione. Senza un laboratorio, senza strumenti e senza un’idea precisa, mi approcciai a “sostegno” avendo fiducia nei racconti che le persone mi avrebbero condiviso. Ero certo che tutto si sarebbe sviluppato da sé. Infatti, iniziai a cercare un spazio dove iniziare a archiviare gli oggetti che mi sarebbero potuti interessare per l’installazione. Passai una giornata a cercare un luogo dove lavorare, la parrocchia aveva difficoltà, i commercianti non avevano spazio e sulla strada di fronte a Lollo, il restauratore, la situazione era pericolosa per il locale che veniva a fare i controlli. Andai a parlare con la "Bottega delle Cose Buone", che era stato uno dei luoghi più colpiti dall’alluvione.

Incontrai Giulia e Gianni, due personaggi autoctoni bolognesi che mi raccontarono tante storie e mi fecero immaginare l’accaduto. Quella sera stavano impastando del pane con una farina speciale arrivata in giornata da un loro amico di un mulino tra la Toscana e l’Umbria. Stavano lavorando per una commissione importante per un hotel stellato che gli aveva chiesto di mandargli delle prove (gratuite) del loro lavoro. Una grande opportunità per Gianni e Giulia.

Mentre aggiungevano l’acqua all’impasto, dalla finestra del retro della bottega sentirono un botto e videro un'esplosione provenire dal cortile interno. Il fiume aveva distrutto la tombatura in cemento ed esso vomitava acqua, fango e legna che si portava dietro. La forza di questa massa distrusse garage, fece muovere putrelle di svariati metri, i motorini sembravano aver perso il loro peso e le macchine si rigiravano come fossero sdraio. Inutile dire che il vetro della finestra da cui Gianni e Giulia vedevano piovere fuori non resistette. Ci vollero pochi minuti prima che tutta la bottega fosse invasa. Il fango trapassò tutto il locale e a fatica riuscirono ad aprire la porta d’uscita, che con il peso della massa di fango si era spanciata verso l’esterno, bloccandosi.

Rimanemmo a parlare a lungo, le persone del quartiere, gli amici e i clienti entravano per salutare, augurare il meglio e portare i più sentiti auguri per la sventura che aveva travolto l’amata coppia. Giulia e Gianni si amavano davvero. Un lato che emerge subito quando si scambiano due parole con loro è proprio questo: si prendono in giro, si insultano, ma poi un sorriso li unisce e una battuta in bolognese stretto fa unire queste due onde in schiuma di risate. Così li ricordo, nella loro bottega sottosopra, abbracciati, guardando il disordine, con la voglia di ricominciare un’altra volta.

Uscì dal locale attonito. A vedere le condizioni della bottega, a sentire le storie che coronavano l’evento e vedere quei due con una forza tremenda, pronti a mordere le assicurazioni e puntare il dito sulle istituzioni che avevano sottovalutato il problema delle tombature, del lavoro e del consumo di suolo che le città stanno affannosamente deturpando, e per non essere intervenuti tempestivamente nell’allarme e nel soccorso.

Tornai il giorno dopo e trovai Gianni e Giulia dietro al bancone, alle prese con le carte burocratiche. Forse l’assicurazione sarebbe riuscita a coprire parte dei danni. Mi si riempì il cuore e andammo a bere un caffè.

Gli raccontai la mia storia, gli dissi che Bologna aveva conquistato una parte del mio cuore e che un altro pezzettino l’avevo lasciato sotto uno dei miei portici preferiti durante gli anni d’Accademia.

Gli raccontai che volevo donare un lavoro ad Andrea Costa e ai volontari che avevano contribuito nel ripristino delle zone e che cercavo un luogo dove assemblare l’installazione. Mi guardarono e con un’infantile umiltà mi dissero che, se mi bastava, potevo utilizzare l’entrata della bottega, che quello che avevano da offrire era quello e che l’avrebbero condiviso con piacere. Mi dissero che molte persone li avevano aiutati ad uscire, anche emotivamente, da quella situazione, ed ora si sentivano pronti ad utilizzare quella gentilezza ricevuta. Mi dissero che la porta non si poteva chiudere perché era completamente dislocata, la serranda anche non toccava il pavimento. Questo mi dissero che mi permetteva di entrare ed uscire quando volevo, con o senza la loro presenza, senza bisogno di chiavi.

Accettai con gran entusiasmo quel piccolo spazio, con una meravigliosa compagnia.

Il giorno dopo mi presentai con dei pasticcini siciliani e loro presero il caffè dal bar accanto, che grazie al patio che avevano costruito di fronte non aveva avuto danni. Facemmo colazione assieme. Le storie e l’energia che avevano in serbo i due erano infinite. Le giornate passavano così: una passeggiata per Bologna e per le zone più colpite, andavo a trovare Giulia e Gianni con cui condividevo un buon caffè, poi uscivo e continuavo la mia ricerca di materiali e storie per le vie colpite. Quando avevo bisogno di strumenti o pareri, andavo a cercarli per le vie. Scoprii, passeggiando, moltissime piccole botteghe che cercai di frequentare il più possibile. Conobbi Lollo e il padre, che gestivano uno spazio dove restauravano mobili in legno. Lollo aveva la mia stessa età, si vedeva che era giovane, ma essendo lui a gestire la baracca, aveva un aspetto più autoritario e serio di un ventinovenne. Quando avevo bisogno di strumenti, mi riferivo a lui, che sempre con gentilezza me li prestava. Conobbi Andrea del bar "Divieto di accesso", che mi propose di installare il lavoro fuori dal suo locale, lo voleva a tutti i costi anche se non aveva visto ancora nulla. Conobbi Fausto, che stava restaurando la porta al di là della strada dalla bottega del pane di Giulia e Gianni. Lo vidi per tre giorni consecutivi e il terzo ci andai a parlare. Mi fece tagliare del ferro lì, sul ciglio della strada, e lo ringraziai dicendogli che avevo apprezzato molto la sua fiducia. Se mi fossi fatto male, sarebbe stata responsabilità sua. Intavolammo un discorso che mi fece restare lì con lui fino al calar del sole. Parlammo di strumenti di carpenteria (di cui entrambi eravamo fanatici) e di responsabilità delle aziende, fino a quando mi disse qualcosa che mi segnò nel profondo. Mi parlò di quanta energia serve per preoccuparsi del farsi male. Mi disse che spesso ci fasciamo la testa con milioni di precauzioni e (soprattutto) preoccupazioni, quando la vita è così fatale e inaspettata. Tirò fuori l’esempio della Toyota Material Handling di Bologna, dove pochi giorni prima c’era stato uno scoppio di un grande boiler che aveva portato alla morte due operai e fatto numerosi feriti. Mi parlava di quanto fosse lunga la procedura per entrare in quel luogo, prendevano moltissime precauzioni prima di far entrare le persone all’interno della fabbrica, eppure nessuno aveva badato al controllo di quell’oggetto posto esternamente, e per questa mancanza, Lorenzo, di 47 anni, non ha potuto incontrare la figlia/il figlio per pochissimi mesi dalla nascita.

Mirella mi accolse nella sua bottega "I Filati di Mirella". Una sera, stanco e indeciso su un dettaglio del lavoro, entrai in questo luogo pieno di cotone a batuffoli di ogni tipo di colore. Mi sembrava di stare in un mondo parallelo, quasi come se in quel luogo varie fiabe avessero preso vita. Mi accolse con un bicchiere di vino bianco davvero squisito e le raccontai i miei dubbi e quello che stavo facendo. Avevo iniziato a cucire i sacchi di juta che avevo raccolto dalla strada, sacchi che erano serviti per arginare acqua e fango dall’entrata delle case, i garage e le attività commerciali.

Avevo bisogno di un punto sicuro e deciso, un punto con cui i sacchi di juta sarebbero rimasti saldi perché li avrei trattati come una pelle in fase di conciatura, tecnica utilizzata fino a prima dell’arrivo delle macchine, quindi avrebbero avuto una tensione verso l’esterno che avrebbe pesato in primis sulle cuciture.

Oltre al tipo di punto, cercavo anche un filo resistente che mi concedesse questa trazione.

Mirella, con una voce pacata, la pazienza di una madre e l’umiltà di chi conosce una tecnica e la vuole tramandare, mi fece vedere un punto semplice da realizzare che non mi avrebbe dato alcun tipo di problema sulla tenuta.

Ripetevo la tecnica imitando quello che faceva, che sembrava tanto semplice mentre cuciva, ma poi, sul pratico, era molto facile invertire lato e fare il movimento speculare e cambiare giro. Mi corresse e appresi il punto fino a farlo mio.

Inoltre, l’idea iniziale era quella di ritagliare i sacchi uniti ad ago e filo e sagomarli a forma di impronta di una mano, perdendo tutte le cuciture esterne già date dalla struttura del sacco. Mirella mi guardò per un momento e mi disse che mi stavo complicando la vita. Che spesso le cose più semplici sono quelle più efficaci. Immediatamente pensai al disegno. Provai ad immaginare i sacchi cuciti tra di loro così com’erano, senza nessun tipo di sagomatura e ritaglio, e a disegnarvi sopra l’impronta a carboncino. Rimasi a ragionare con Mirella su questo per un po’, poi corsi al forno e buttai subito l’idea su carta fino a sera inoltrata.

Passeggiando per quelle vie, si stava inconsciamente creando un simbolo nella mia mente che andava a rappresentare quelle giornate. Chi si era messo a disposizione nel ripristino dei vari spazi colpiti dall’alluvione ne usciva sempre imbrattato di fango da testa a piedi. Mani e calzari erano le prime a diventare mezze e le impronte scivolavano via dai corpi sulle superfici pulite. Le impronte delle mani sui muri mi fecero però più impressione. Riuscivo a vedere i volontari appoggiarsi alla parete per alzare pesi, come per darsi forza. Vedevo i volontari sporcare le pareti dando una manata contro il muro, quasi come per dire “io c’ero”. E quell'“Io” si sfumava nell’impronta univoca della mano a cinque dita, senza volto e senza nome.

Solidarity Day in Bologna: The Neighborhood's Response to the Flood of October 19-20, 2024

The flood that struck Emilia-Romagna between October 19 and 20, 2024, devastated numerous municipalities, including Bologna and its metropolitan area. It caused significant damage due to the overflowing of rivers and streams and the pressure built up in underground canals. A young life was lost, and thousands of people were forced to leave their homes.

The intense rainfall, which delivered the equivalent of two months' worth of precipitation in just a few hours, highlighted the increasing vulnerability of the territory, exacerbated by ongoing urbanization and soil consumption. This phenomenon, worsened by climate change, has become a tragic recurring reality, as evidenced by the series of floods that have affected the region in previous years.

In response to the tragedy, the volunteers of Bologna were called to unite in a powerful act of solidarity. On November 10, 2024, via Andrea Costa was transformed into a fundraising space, thanks to the street festival organized to support families affected by the flood and to offer a tangible sign of solidarity. The event represented the continuation of civic commitment, with thousands of people actively involved in the days following the disaster, joining forces to rebuild the city and help people recover from the devastation.

Support was organized on via Andrea Costa, right in one of the most affected areas, between two sections where the river had overflowed, causing the concrete tomb to burst. There, among people waiting for insurance answers to find out if the damage could be partially reimbursed, and the debris spilling over the sidewalks, still dripping with mud, we gathered.

We went down into the cellars, and there was a mark painted on the wall, a line that marked the water level: it reached up to the neck. Giorgio, a resident of via del Q, whom we were sent to help with clearing the cellars, told us that they had been lucky in their building. Somehow, the water had found an escape route, and within a few hours of the flood, it had receded, leaving only inches of mud. Many of us arrived. In those days, solidarity worked miracles. The parish became the base camp, with refreshment points, tables with boots, shoe covers, gloves, areas to wash off the mud, and spaces where volunteers gathered to be sent where the need was greatest. One of the miracles of those days was the breaking down of ideological walls: seeing the PLAT (Social Intervention Platform) groups, who had been working on the occupation of via dei Carracci Casa Comune — where they had provided housing to dozens of homeless families — alongside the parish scouts, with the priest on the frontlines, was truly unbelievable.

Even in via del Q, the situation was difficult, but the team I was with had an impressive number of people. We formed chains, with few staying in the cellars while others passed items to be thrown out, stacking them along the road. We arrived at Giorgio's, and the volunteers were still on their way. Along the road, a cellar that had not been damaged offered us wine, seeing us all covered in mud and recognizing us as volunteers. Before starting the clearing, we stopped to chat with Giorgio, who showed us his cellars: one was filled with more recent items, and the other with barrels, bottles, and all the wine-making equipment he kept for memories.

The tone with which he spoke created a bittersweet warmth in our hearts, almost burning. Everything was to be thrown away. We started the chain, while more volunteers joined in. Giorgio stayed close, watching what we touched and what we threw away, as each item for him was a piece of life, one of those memories carefully kept, now submerged by water and mud, taken away by the young men and women. He resigned himself to the fact that most things had to be discarded, but he told us with a smile that he had wanted to clean up for a long time and that perhaps this was the right occasion. He said it with a smile, happy to share this moment with us. He realized he was not alone in clearing the cellar, as dozens of young people were there beside him. That realization reflected on his face in a specific moment, and from there, his eyes began to shine.

A few weeks later, I returned to be part of the solidarity fundraising day for Andrea Costa and its inhabitants. I spent a week walking those streets, talking to shopkeepers, residents, and passersby. I decided to create a piece of work there, even though I had been asked to make something visible on the street that could connect with people and therefore needed a certain size. Without a workshop, tools, or a clear idea, I approached "support" trusting in the stories the people would share with me. I was sure everything would unfold on its own. In fact, I began looking for a space where I could start storing the objects that might be of interest for the installation. I spent a day searching for a place to work, the parish had difficulties, the shopkeepers had no space, and on the street in front of Lollo, the restorer, the situation was dangerous for the shop where inspections were being conducted. I went to speak with the "Bottega delle Cose Buone," one of the places most affected by the flood.

I met Giulia and Gianni, two local Bologna residents who shared many stories and helped me imagine what had happened. That evening, they were kneading bread with special flour that had just arrived from a friend of theirs who ran a mill between Tuscany and Umbria. They were working on an important commission for a starred hotel that had asked them to send free samples of their work. A great opportunity for Gianni and Giulia.

As they added water to the dough, they heard a loud bang and saw an explosion coming from the courtyard behind the shop. The river had destroyed the concrete tomb and was spewing water, mud, and wood it had carried with it. The force of this mass destroyed garages, moved steel beams several meters, motorcycles lost their weight, and cars spun around like lounge chairs. Needless to say, the window through which Gianni and Giulia had been watching the rainstorm did not hold up. It took only a few minutes for the whole shop to be flooded. The mud rushed through the whole place, and they struggled to open the exit door, which, with the weight of the mud, had swollen outward and got stuck.

We stayed to talk for a long time, people from the neighborhood, friends, and customers came in to greet, wish the best, and offer their condolences for the misfortune that had struck this beloved couple. Giulia and Gianni truly loved each other. One thing that immediately stood out when talking to them was this: they teased each other, insulted each other, but then a smile would unite them, and a joke in thick Bolognese would bring these two waves of laughter together. This is how I remember them, in their overturned shop, embracing, looking at the mess, ready to start again.

I left the place stunned. Seeing the conditions of the shop, hearing the stories surrounding the event, and witnessing those two with such strength, ready to take on the insurance companies and point fingers at the institutions that had underestimated the problem of tombs, work, and soil consumption, which cities are desperately defacing, for not intervening promptly in the alarm and rescue efforts.

The next day, I returned and found Gianni and Giulia behind the counter, dealing with paperwork. Perhaps the insurance would cover part of the damage. My heart swelled, and we went out for coffee.

I shared my story with them, telling them that Bologna had won a part of my heart and that I had left another piece under one of my favorite arcades during my Academy years.

I told them I wanted to donate a piece of work to Andrea Costa and the volunteers who had contributed to restoring the affected areas and that I was looking for a place to assemble the installation. They looked at me, and with childlike humility, told me that if I needed it, I could use the entrance of the shop; what they had to offer was that, and they would be happy to share it. They told me that many people had helped them get out of the situation, even emotionally, and now they felt ready to return that kindness. They told me the door couldn’t close because it was completely misaligned, and the roller shutter didn’t touch the floor. They said this allowed me to come and go as I wished, with or without their presence, without needing keys.

I enthusiastically accepted that small space, with wonderful company.

The next day, I showed up with Sicilian pastries, and they got their coffee from the bar next door, which, thanks to the patio they had built, had not been damaged. We had breakfast together. The stories and energy they had were endless. The days passed like this: a walk through Bologna and the hardest-hit areas, a visit to Giulia and Gianni to share a good coffee, and then I’d go out and continue my search for materials and stories on the affected streets. When I needed tools or advice, I went looking for them in the streets. I discovered, walking around, many small shops I tried to visit as much as possible. I met Lollo and his father, who ran a place where they restored wooden furniture. Lollo was my age, but since he managed the business, he had a more authoritative and serious look than a 29-year-old. When I needed tools, I referred to him, and he always kindly lent them to me. I met Andrea from the "Divieto di accesso" bar, who suggested I install my work outside his shop; he wanted it at all costs even though he hadn’t seen anything yet. I met Fausto, who was restoring a door across the street from Giulia and Gianni’s bread shop. I saw him for three consecutive days, and on the third, I went to talk to him. He had me cut some metal there on the edge of the street, and I thanked him, telling him I appreciated his trust. If I had hurt myself, it would have been his responsibility. We started a conversation that kept me there until sundown. We talked about carpentry tools (both of us were fanatics) and corporate responsibility, until he said something that marked me deeply. He told me how much energy we waste worrying about getting hurt. He said we often wrap our heads with millions of precautions and (especially) worries when life is so fatal and unpredictable. He gave the example of Toyota Material Handling in Bologna, where a few days before, a large boiler explosion had killed two workers and injured many others. He spoke of how long the procedure was to enter that place; they took many precautions before allowing people inside the factory, but no one had checked that external object, and because of that negligence, Lorenzo, aged 47, didn’t get to meet his child for just a few months after their birth.

Mirella welcomed me into her shop "I Filati di Mirella." One evening, tired and undecided about a detail of my work, I entered this place full of cotton balls of every color. It felt like I was in a parallel world, almost as if several fairy tales had come to life there. She greeted me with a glass of exquisite white wine, and I told her my doubts and what I was doing. I had started sewing the burlap sacks I had picked up from the street, sacks that had been used to block water and mud from entering homes, garages, and businesses.

I needed a secure and decided stitch, one that would keep the burlap steady because I was going to treat it like leather during the tanning process, a technique used before the arrival of machines. It would have an outward tension, which would first affect the stitching.

That night, in the warmth of the shop, I told her I was working on a tribute to the community’s commitment, their mutual support. To my surprise, she immediately embraced my project with enthusiasm, telling me, “Maybe this piece will make people think of those who fought for us.”

Materials: Jute sacks, charcoal, iron, wood, blanket.

Dimensions: 200 x250 x 30 cm

Bologna

2024